The Heartbeat of Stellar Corpses

In 1967, astronomer Jocelyn Bell detected strange but periodic signals from outer space, briefly mistaking them for extraterrestrial life. She jokingly nicknamed the source ‘Little Green Men’ (LGM-1). These mysterious signals were the first discovered pulsars—cosmic “heartbeats” of stellar corpses.

Death is an inevitable part of nature — often feared as life’s most painful phase. Yet it was through such an ending that Siddharta transformed into Gautama Buddha, guiding humanity toward acceptance and wonder. In my previous blog I portrayed how ethereal stellar deaths can be. If stellar deaths can be beautiful, its afterlife can be even more surprising! Now, I invite you to behold the stellar corpses that, far from lifeless, still pulse with photonic heartbeats.

“Even in death, stars refuse silence — they leave behind a heartbeat of light.”

Discovery Of The Little Green Men

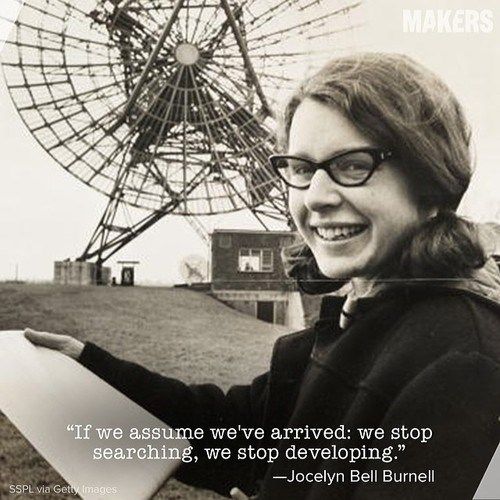

In 1967, a newly commissioned radio telescope was set up at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory near Cambridge, UK. Its purpose was to study scintillations - the twinkling of radio sources caused by the solar wind — to better understand space weather. A young astronomer, Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who had helped build the telescope, used it to study quasars for her Ph.D. thesis. On August 6, she noticed something unusual: strange radio signals recorded by the telescope. When she analysed them, she was certain they could not be quasars — the signals were far too periodic.

She reported the anomaly to her supervisor, Prof. Antony Hewish, who at first shrugged it off as radio interference. But with repeated observations, Bell Burnell confirmed the signals always came from the same patch of sky. Theories multiplied. Could this be some new astrophysical object? Or, as one half-serious suggestion went, could it be evidence of extraterrestrials trying to contact us?

The source was jokingly nicknamed LGM-1 — Little Green Men 1. And when more signals were found, it became clear: this was not interference, nor aliens — but the birth of a whole new class of cosmic object.

Jocelyn Bell posing with the Interplanetary Scintillations Array Radio Telescope that she built. Image Credits: Science Museum Group

Jocelyn Bell posing with the Interplanetary Scintillations Array Radio Telescope that she built. Image Credits: Science Museum Group

Clues in Jocelyn’s Observations

At first, the tiny sharp pulses were thought to be radio interference — stray signals from nearby electronics or a radio transmitter. What, then, suggested to Jocelyn that it was not merely noise? One crucial observation supported her claim that the signal was celestial: the pulses reappeared at the same sidereal time each day.

What is a sidereal day? Just as a solar day measures the rising and setting of our nearest star — the Sun — a sidereal day measures the rising and setting of the background stars. A sidereal day is about four minutes shorter than a solar day. Thus, the strange periodic signal rose and set with the stars, not with Earth’s rotation, showing that it could not be radio interference.

If they were celestial, then why was the LGM hypothesis eventually withdrawn? The observed signal was found to be broadband — spanning a wide range of radio wavelengths — making it highly unlikely to be a communication signal. Furthermore, had it been from a transmitter in a distant Earth-like planet, slight variations due to Doppler shift would have been observed, but none were. Later, similar signals were detected from other parts of the sky. If these were truly LGM signals, why would they all produce identical patterns?

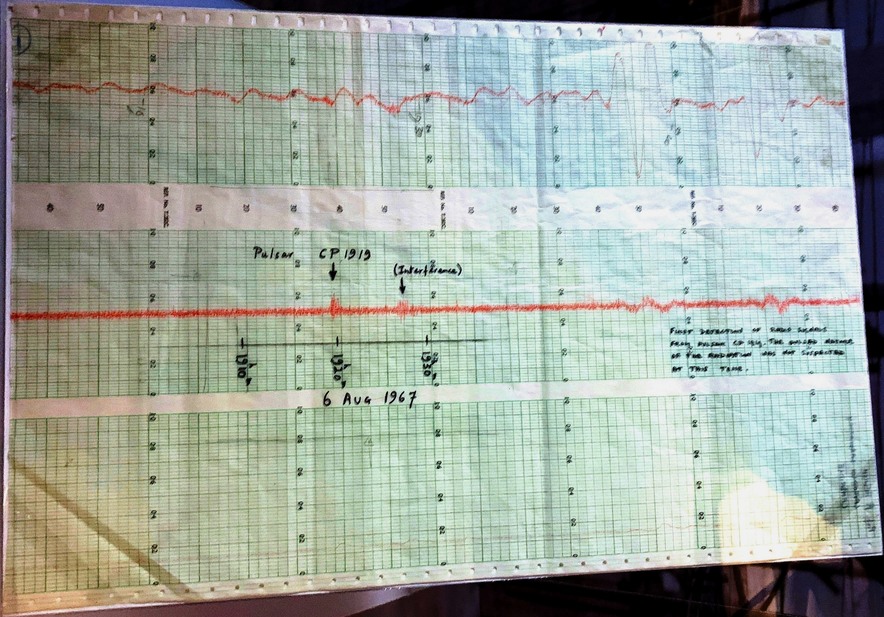

Chart recording with the radio signal from the pulsar that Jocelyn discovered. Image Credits: Institute of Mathematical Sciences

Chart recording with the radio signal from the pulsar that Jocelyn discovered. Image Credits: Institute of Mathematical Sciences

Taken together, these observations pointed away from extraterrestrials and toward natural astronomical sources, particularly stellar remnants.

Search For The Right Candidate

Another interesting point is that the sources were hundreds to thousands of light-years away, but dispersed around the galactic plane — narrowing it down to stellar remnants and ruling out the possibility of extragalactic objects. At the time, astrophysicists were working to understand stellar dynamics, gradually piecing together the stellar life cycle. The only known and observed stellar corpse then was a white dwarf, and theories suggested that such objects were compact enough to rotate or even pulsate, potentially giving off short pulses.

However, Jocelyn’s supervisor was not convinced that the source could be a rotating white dwarf. The periodicity of the signals was too short — measured in milliseconds — for a white dwarf to rotate at such speeds without breaking apart. The emissions were brief and highly energetic, which would be impossible for a white dwarf to produce given its limited gravity and magnetic field strength. Theoretical models of another very interesting compact object fit the data perfectly, and subsequent observations confirmed their existence. These compact objects are called neutron stars, and the ones that emit regular, rhythmic pulses of radiation earned the name pulsars. These pulsars are not just inert stellar remnants — they continue to communicate with the cosmos, their rhythm echoing across light-years.

Pulsar as depicted by NASA. GIF Credits: NASA

Pulsar as depicted by NASA. GIF Credits: NASA

Pulsars: The Living Afterlife

But you may still be wondering: how can something so dead appear so alive? Let’s tackle those doubts one by one.

How can a dead star emit light?

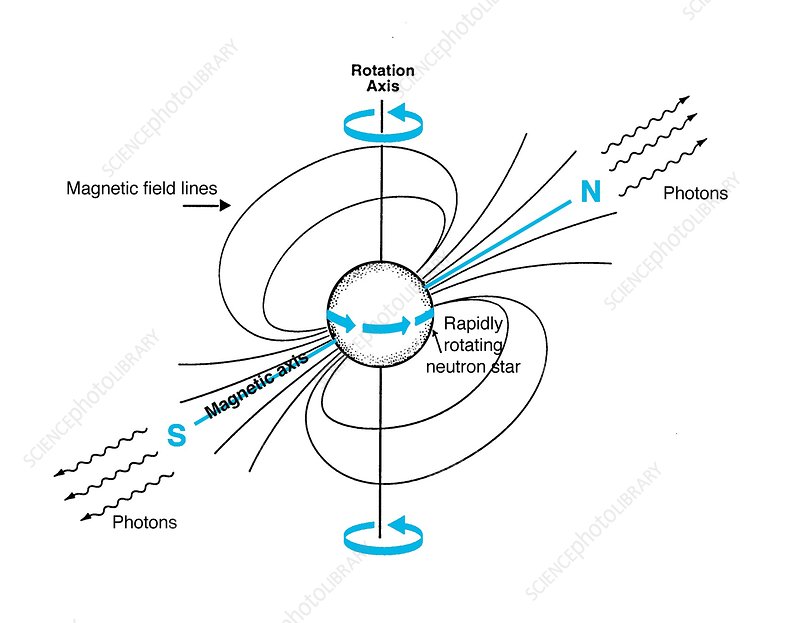

Even though nuclear fusion has ceased, compact objects like neutron stars rotate incredibly fast (quick experiment: try spinning on a rolling chair with your limbs extended, then fold them in to see the speed increase!). Coupled with immense magnetic fields, this rotation accelerates charged particles, producing beams of radiation. As these beams sweep across Earth, we detect them as the characteristic pulses of a pulsar.

While matter is held together against gravity by nuclear fusion, how do these corpses exist effortlessly?

To understand this, we must probe inside a neutron star. After a supernova, the core collapses into an ultra-dense ball of neutrons. These neutrons are held apart by neutron degeneracy pressure, a quantum effect strong enough to balance the intense inward pull of gravity. This is why these stellar remnants remain stable, despite their extreme density.

A more scientific depiction of pulsar dynamics. Image Credits: Science Photo Library

A more scientific depiction of pulsar dynamics. Image Credits: Science Photo Library

Are all neutron stars pulsars?

Not quite. Only neutron stars whose magnetic axis is misaligned with their rotation axis produce beams that sweep across Earth. Others exist silently, invisible to us, even though they are physically the same as pulsars.

What happens to pulsars over time?

Over millions of years, pulsars gradually lose rotational energy. Their pulses weaken, and eventually many become “dead” neutron stars — still compact, but no longer emitting detectable beams. These quiet remnants quietly complete the last stage of their stellar afterlife.

While Jocelyn’s observations played a pivotal role in 20th-century astronomy, she herself is an inspiring figure. She proved to the world that women are equally entitled to dream and achieve big. Her hard work and perseverance to pursue the cosmos, like that of many other successful women in astronomy, keep fueling me to work my way toward the stars! Here are some interesting reads I found while writing this blog. I highly recommend you check them out:

- An excerpt from the book: The Sky Is For Everyone - Women Astronomers In Their Own Words

- Quora Answer from the member of the same research group as Jocelyn

Pulsars show us that even in death, stars keep a heartbeat. But not all remnants are so kind — some blaze briefly, destructively, like cosmic supervillains. Meet the white dwarf in the next chapter of this stellar tale.